|

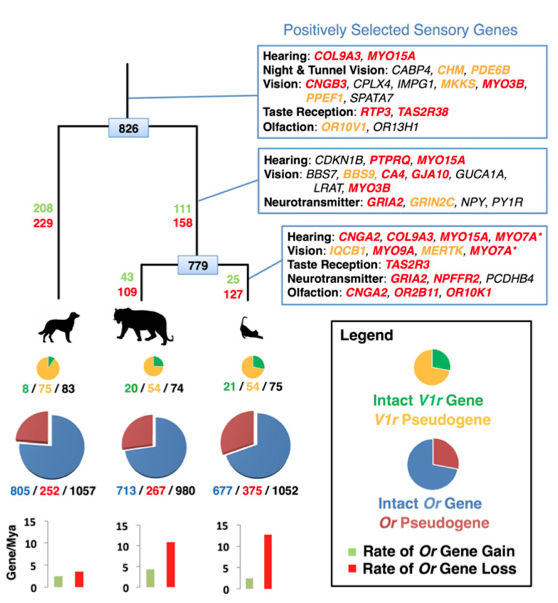

This my second paper highlight and the choice for this week was quite easy. I'm very happy to briefly discuss a paper recently published in PNAS by a friend of mine, Mike Montague at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. Mike and I were graduate students together at NYU and it's great to see his hard work published. Journal reference: Montague et al. (2014) Comparative analysis of the domestic cat genome reveals genetic signatures underlying feline biology and domestication, PNAS (early edition) (DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1410083111) What's about? The paper addressed a very interesting question regarding the domestication of cats. As we all know many animals underwent artificial selection as a consequence of domestication by humans. However, while animals like dogs had a long domestication history, likely focused on selecting specific physical characteristics, cats remain quite similar to their wild relatives. So what actually happened during this relatively recent domestication process? Which specific gene families showed evidence of selection in the cat genome? To answer these questions, Mike and colleagues sequenced the entire genome of a domestic cat and compared it with other mammalian genomes including tiger, dog, cow, and human. The results of this study are probably to be considered preliminary but very interesting. The authors found significant differences in the sensory systems of domestic cats. In particular they... [... ] observed an evolutionary trade-off between functional olfactory and vomeronasal receptor gene repertoires in the cat and dog genomes, with an expansion of the feline chemosensory system for detecting pheromones at the expense of odorant detection. I find this result extremely fascinating, not only because I have a very strong interest in the evolution of sensory systems, but also because it supports the importance of pheromones in socio-chemical communication in cats. Other important finding was the identification of positive selection in genes involved in lipid metabolism probably related to adaptations to a hypercarnivorous diet. Finally, the authors found that, compared to both wild cats and non-felid carnivores, domestic cats show an accelerated evolution in genes... ...associated with gene knockout models affecting memory, fear-conditioning behavior, and stimulus-reward learning, and potentially point to the processes by which cats became domesticated. Yeah basically those genes that - possibly - made your kitty a little bit less wild!

Why is it important? This study represents an important step towards a better understanding of the domestication process. Especially it suggests that the main force in driving the domestication process in wild cats was the selection for docility. In contrast to other animals, such as dogs, cats have a quite recent domestication history and likely not as intense. The domestication process for cats was mainly a consequence of becoming accustomed to humans for food rewards. This, together with the limited isolation with wild populations (a domestic cat is not that different from a wild one after all) might explain why your cat still remains a little bit feral. Curiousity. The animal used to sequence the entire genome was a female Abyssinian cat named “Cinnamon.”

1 Comment

My first paper highlight (and first post on this new blog) is a recent study on bat phylogenomics published on Science this week. Journal reference: Misof et al. (2014) Phylogenomics resolves the timing and pattern of insect evolution, Science 346, 763 (DOI: 10.1126/science.1257570) What's about? Misof and colleagues inferred the phylogeny of insects from 1478 protein-coding genes by sequencing 2.5 gigabases (Gb) of cDNA from over a hundred insect species, including all extant insect orders. Their results strongly suggest an origin of insects in the Early Ordovician (around 479 million years ago), and probably more interesting the evolution of insect flight to the Early Devonian (~406 Ma), after the establishment of complex terrestrial ecosystems. Another interesting results was about the radiation of parasitic lice: We estimated that the radiation of parasitic lice occurred ~53 Ma (CI 67 to 46 Ma), which implies that they diversified well after the emergence of their avian and mammalian hosts in the Late Cretaceous–Early Eocene and contradicts the hypothesis that parasitic lice originated on feathered theropod dinosaurs ~130 Ma. Why is it important? This study represents the largest phylogeny for insects to date. It clearly represents a major step towards a better understanding of the tree of life. Insects are the most speciose group of animals and this study will clearly provide a critical phylogenetic backbone for future studies about adaptation, morphology and genomics. Curiousity. In a recent post, Naturejobs listed some of the main features a paper should have to publish big (yes, like Nature and Science). Besides good science (but I guess that was quite obvious), a big stress was put on the importance of the paper title: Don’t underestimate the importance of a good title and abstract, says Dean. These short blocks of text — often the final consideration when constructing a paper — will receive far more views than the paper itself. They should be used as a hook, to pull readers (and editors) in. This means not using superfluous, specialised jargon, especially in the headline and abstract. The word "resolves" in the paper by Misof and colleagues clearly fulfilled the requirements of a powerful and effective title...and Science it was indeed!

|

AuthorA simple blog about science and my research. New papers published, field trips, and interesting news to train a little bit my writing skills. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed